MOSTRA

INFO E MATERIALI

INGRESSO LIBERO

Per info e prenotazione visita gratuita: 3420771754

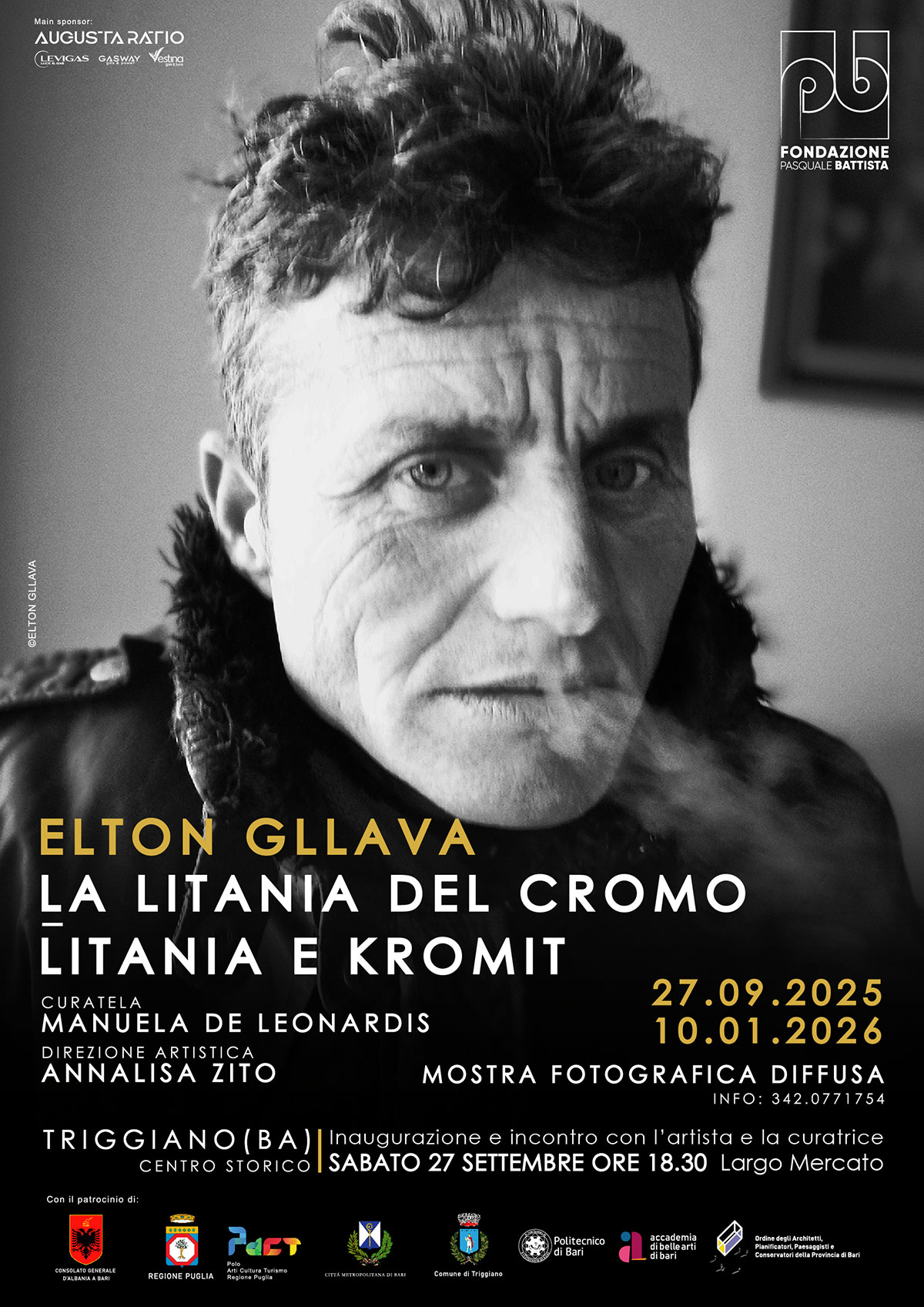

Elton Gllava. La litania del cromo | Litania e kromit (Manuela De Leonardis)

«Il cromo era uno dei pochi beni preziosi che l’Albania, chiusa a quasi tutto il mondo, poteva usare come merce di scambio. La realtà di allora e di adesso, è che il lavoro in miniera è un lavoro durissimo», scrive Elton Gllava nel libro Bulqizë (Postcart Edizioni, 2019). Nel 2013 a portare il fotografo albanese nel paese di Bulqizë, nella parte orientale dell’Albania – quasi al confine con la Macedonia – della gente che lo abita e delle sue miniere di cromo è la notizia degli scioperi della fame dei minatori. Non è una novità: da decenni, periodicamente, i minatori fermano il lavoro sottoterra per manifestare per un salario più equo, la sicurezza sul lavoro, la dignità di esseri umani. Terzo produttore mondiale di cromo (le miniere di cromo furono scoperte nel 1939 quando il paese era sotto l’occupazione dell’Italia fascista), l’Albania è l’unica nazione europea con un numero così elevato di riserve di questo minerale prezioso impiegato per molteplici usi. Il fotografo che vive in Italia dall’inizio degli anni Novanta decide, quindi, di recarsi a Bulqizë: in questa curiosità c’è anche il desiderio di scoprire il suo paese attraverso le sue storie. Pur parlando la stessa lingua, a Bulqizë si sente uno straniero. La città è incapsulata tra le montagne, immersa in un passato doloroso come quello della miniera Fitore aperta nel ’48, dove negli anni più duri del regime comunista – tra il 1954 e il 1982 – ben 81 prigionieri politici costretti ai lavori forzati persero la vita. La prima volta Elton Gllava si ferma a Bulqizë solo per pochi giorni e con la sua Hasselblad inizia a scattare intorno a sé con estrema libertà. È aperto a tutte le novità che intercetta, attirato dalla semplicità dei gesti della gente nella quotidianità ma anche dalla crudezza del lavoro nelle miniere e dall’atmosfera che si respira in quel posto remoto. Solo quando rientra a Roma, dopo aver sviluppato i rullini e stampato le fotografie, capisce che ha senso continuare a lavorare a quel progetto per approfondire la storia dei minatori così strettamente connessa con quella del territorio. Un lavoro durissimo, quello nelle miniere, che prende ma non restituisce eppure, come sente dire spesso, «se non ci fosse stato il cromo, i corvi avrebbero cantato.» Anche per Gllava, come per molti altri fotografi, la macchina fotografica è uno strumento d’indagine irrinunciabile. Nel puntare l’obiettivo tutt’intorno a lui, piano piano si delinea la consapevolezza che fotografare è anche l’occasione per conoscere una parte di sé. Il tempo è un altro elemento significativo nel dare il ritmo alla narrazione di cui si fa portavoce. Nei cinque anni in cui realizza il progetto egli torna periodicamente in paese nell’alternarsi delle stagioni. L’inverno è particolarmente duro a Bulqizë: è netto il contrasto tra il freddo glaciale dell’esterno e il caldo insopportabile delle viscere delle montagne. Anche queste sensazioni entrano nel suo racconto fotografico, come la luce che accarezza i giorni nel loro susseguirsi, il grigiore degli edifici e l’oscurità compatta dei tunnel delle miniere illuminati dalle lampade a carburo. Il bianco e nero, in tutta la sua potenzialità metaforica, con i chiaroscuri esasperati è per l’autore il linguaggio più consono a cui affidare esteticamente la tensione, il dramma, i silenzi eloquenti. La fotografia in bianco e nero, del resto, enfatizza il sentimento nostalgico legato al ricordo. Oltre 126 entità minerarie sono attive a Bulqizë e la maggior parte dei 12 mila abitanti lavorano in miniera utilizzando attrezzature e sistemi obsoleti che mettono a rischio la loro vita stessa. La poesia del bianco e nero di Gllava, però, è tutt’altro che edulcorata nel restituire la durezza e la tragicità di un tempo presente. Con la macchina fotografica al collo – una presenza visibilmente ingombrante – egli si addentra nei tunnel della città sotterranea, scendendo in profondità sotto lo sguardo timoroso dei dirigenti delle miniere. Ciò che non è inquadrato dal mirino è facilmente intuibile. Egli fotografa i documenti antichi, cartacei e fotografici, che trova nel Palazzo della Cultura, lasciati nell’incuria in due scatole di cartone poggiate sul pavimento tra la polvere e l’umidità. Anche questi documenti riguardano i minatori. Gllava, intanto, continua a fotografare i volti della gente che incontra in paese, camminando tra i branchi di cani randagi. Le donne sono le più reticenti nel lasciarsi fotografare. Il progetto si concluderà dopo 5 anni, ma ne trascorrono due prima che egli si renda conto che c’è qualcosa che gli sfugge. Attribuisce dubbi e resistenze alle persone che frequenta e fotografa, finché non si rende conto che è proprio lui, inconsciamente, ad avere i preconcetti. «La macchina fotografica è una scusa per relazionarmi all’altro,» – afferma il fotografo «per esprimere la voglia di conoscenza, per approcciarmi al mondo guardandolo da diverse prospettive ma anche per aprirmi e scoprire me stesso.»

Elton Gllava. The Litany of Chromium | Litania e kromit (Manuela De Leonardis)

“Chromium was one of the few precious goods that Albania, isolated from almost the entire world, could use as a bargaining chip. The reality then, as now, is that mining is extremely hard work” writes Elton Gllava in his book Bulqizë (Postcart Edizioni, 2019). In 2013, it was the news of miners’ hunger strikes that brought the Albanian photographer to the town of Bulqizë, in eastern Albania near the Macedonian border—to the people who live there and to its chromium mines. It was nothing new: for decades, miners have periodically gone on strike to protest for fair wages, workplace safety, and human dignity. Albania, the third-largest chromium producer in the world (the chromium mines were discovered in 1939 during the Italian fascist occupation), is the only European nation with such a high concentration of this valuable mineral, which has many uses. The photographer, who has lived in Italy since the early 1990s, decided to travel to Bulqizë. His curiosity was driven not only by interest in current events but also by a desire to discover his own country through its stories. Although he speaks the same language, Gllava feels like a foreigner in Bulqizë. The city is nestled between mountains, steeped in a painful past—like the Fitore mine, opened in 1948, where during the harshest years of the communist regime (1954 to 1982), 81 political prisoners forced into labour lost their lives. The first time Gllava visits Bulqizë, he stays only a few days, freely taking photos with his Hasselblad. He is open to everything he encounters, drawn by the simplicity of people’s daily gestures, the harshness of the mining work, and the atmosphere that pervades this remote place. It’s only when he returns to Rome and develops the film and prints the photographs that he realizes there is value in continuing the project to explore the miners’ history so deeply tied to that of the land. Mining is grueling work—demanding but giving little in return. And yet, as he hears repeatedly, “hadn’t it been for the chromium, the crows would have sung.” For Gllava, as for many photographers, the camera is an essential tool for investigation. As he frames his surroundings, a growing awareness emerges: photography is also a way of getting to know a part of himself. Time is another key element shaping the rhythm of the narrative he seeks to convey. Over five years, he returns periodically to Bulqizë through the changing seasons. Winters there are especially harsh: the stark contrast between the freezing cold outside and the unbearable heat deep within the mountains becomes part of his photographic storytelling, along with the light brushing over the days, the greyness of the buildings, and the dense darkness of mine tunnels lit by carbide lamps. Black and white—with all its metaphorical power and heightened contrasts—is the language Gllava chooses to express the tension, drama, and eloquent silences. Black-and-white photography also emphasizes the nostalgic feeling linked to memory. More than 126 mining sites are active in Bulqizë, and most of the town’s 12,000 inhabitants work in the mines using outdated equipment and systems that put their lives at risk. Yet the poetry of Gllava’s black-and-white imagery does nothing to soften the harshness or the tragic nature of the present. With his camera—an obviously conspicuous presence—around his neck, he ventures into the tunnels of the underground city, descending under the wary eyes of mine managers. What isn’t captured by the lens is still easy to imagine. He photographs old documents—paper and photographic—that he finds in the Palace of Culture, left neglected in two cardboard boxes on the floor, surrounded by dust and dampness. These, too, tell the story of the miners. Meanwhile, Gllava continues to photograph the faces of people he meets in town, walking among packs of stray dogs. Women are the most reluctant to be photographed. The project concludes after five years, but two more pass before Gllava realizes something is missing. He attributes the doubts and resistance to the people he’s photographing, until he comes to see that it is actually he himself, unconsciously, who holds preconceived notions. “The camera is an excuse to relate to others,” the photographer says, “to express the desire for understanding, to engage with the world by seeing it from different perspectives, and also to open up and discover myself.”

STAFF MOSTRA

Direzione artistica

Annalisa zito

Curatela

Manuela De Leonardis

Progettazione e allestimento

Arch. Dino Lorusso

Project Management

Cinzia Campobasso

Coordinamento tecnico

Ninni Castrovilli e

Lisabeth Ciavarella

Ufficio Stampa

Tommaso Forte

Segreteria organizzativa

Claudia Lopuzzo

Progetto grafico

Stefano Quagliarella

Progetto sito web

Officina Réclame

Allestimento e montaggio opere

We Makers

FONDAZIONE PASQUALE BATTISTA

Presidente

Flavio Augusto Battista

Vicepresidente

Claudio Battista

Consigliere di Amministrazione

Edoardo Fulvio Battista

Direttrice

Annalisa Zito

Project Manager Area Ricerca e Sviluppo

Cinzia Campobasso

Cultural Manager

Rosanna Carabellese

Cultural Project Manager

Luca Carnicelli

Marketing & Communication Manager

Lisa Andriani

un progetto di

in collaborazione con

MAIN SPONSOR

Patrocini

Progetto grafico

Stefano Quagliarella